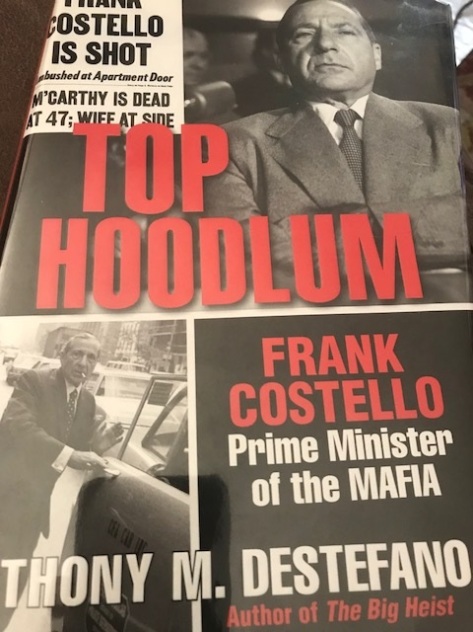

The raspy voice that Marlon Brand employed in his portrayal of Don Vito Corleone in “The Godfather” was said to have been the result of his study of the tapes of crime boss Frank Costello, who suffered from several different throat ailments, testimony before a congressional committee in 1951 that heard testimony from him and several other organized crime figures in the U. S. Costello’s story is told in the recently published “Top Hoodlum,” which takes its title from J. Edgar Hoover’s one time designation of Costello. And the gangster was often described in the post war era as “The prime minister of the Underworld” due to his ability to peacefully settle disputed between the five Mafia families of New York City and their counterparts in other parts of the nation. Yet as Destefano’s research makes clear, that title did not do him justice, since his influence extended throughout New York and other parts of the nation, and he attended the Democratic National Convention that nominated Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1932. Costello, who had interests in numerous popular nightclubs in New York City, was said to have helped some attorneys obtain coveted judgeships and was often seen at those places dining with a variety of celebrities and politicians. The heroin dealer who was seeking to enlist the support of Don Corleone in “The Godfather” novel and movie tells him in a meeting that it is said that Don Corleone has more judges in his pocket than a shoe shiner has coins in his purse, and that may have been inspired by the power that Costello was said to wield in the courtrooms of New York City.

Costello was brought to New York City by his immigrant parents from Sicily at the age of four in 1895 and was initially known as Francisco Castiglia but Anglicized his name to Frank Costello in his youth when he began his career as a bootlegger during Prohibition and later branched out into gambling. Destefano details how Costello expanded his operations into New Orleans, Louisiana, in the 1930’s where he introduced his slot machines to that fabled city and also became a partner in a gambling place that was located in an adjacent locale. Costello later said in 1940 and subsequently that it was with the blessing of then Senator Huey Long of Louisiana- who had been assassinated in 1935- that he did so, and that alleged association has often been cited by those who have sought to disparage Long. But Destefano details that Long’s most authoritative biographer, T. Harry Williams, pointed out that at that time New Orleans was led by Mayor Semmes Walmsley, who was a sworn enemy of Long, and would have rushed to remove any such devices that were put in place by any party allied with Long, and Williams perceptively concluded that the wily Costello’s “Over eagerness to connect his entrance into the New Orleans slot-machine business with Huey suggests that he was trying to shield somebody who had permitted him to come into the city later.” Costello also had a variety of legitimate interests, that the author relates included interests in oil wells in Oklahoma and Texas.

Costello’s memorable appearance before the U.S. Congress is recounted in considerable detail by the author, and before he began to testify Costello’s long time attorney, George Wolf, insisted that his client’s face not be shown on the television cameras that were present. That request resulted in the cameras filming his hands that he nervously rubbed together when he wasn’t tapping his finger on the table as his raspy voice was recorded in heated exchange with several of the senators present. The New York Time’s television reporter would imaginatively describe the image that was played on thousands of television sets throughout the nation as “video’s first ballet of the hands.’ And Costello’s resulting notoriety resulted in the federal government pursuing him on numerous charges, including income tax evasion, and making false statements when he obtained US citizenship and he served time in federal prisons as a result.

In 1957 Costello was wounded in an assassination attempt made by Vincent “Chin” Gigante, who decades later would be famous as the “Crazy Don” who feigned mental illness by walking in New York City in his bathrobe muttering to himself. He subsequently retired and let a quiet life with his long time wife Loretta. No children were born of their marriage. He died in 1973 at the age of 83 and was buried in a mausoleum that bore his last name located in a cemetery in the Bronx Borough of Queens. His widow subsequently relocated to New Orleans, Louisiana, where it was reported in the local media that she was living in greatly reduced circumstances with relatives who resided there and provided her with financial support.

But in 1974 the brass doors on Costello’s mausoleum was blown off supposedly on the orders of mobster Carmine Galante as a sign of disrespect towards Frank Costello.